Archive

Theory of Mind, Atheism and Religion – Part 1

When I was a freshmen in college I took a course that Illinois Wesleyan required to teach us freshmen how to write: the gateway colloquium. The one I had was with a professor who spent the entire time teaching us to engage in intelligent discourse, both in written papers and in-class discussion. One of the papers I wrote came about after the professor e-mailed us an article entitled “Is God an Accident”. In the paper I wrote in response, I explored the idea that perhaps religion is a social construct but that, more importantly, I was not “wired” to believe in God.

The brief synopsis came from when my professor spoke about the idea of God being love—that people with intense religious experiences could use only the term “love” to really explain the way it felt. In exploring this idea, along with the ideas that Paul Bloom explores in his article, I came to the conclusion that perhaps for all of the social components creating religion the most important part is, in fact, the ability of the person to be religious.

Since that time I’ve had a lot more time to learn about the cognitive and neurological sciences, and though I am still far from being even close to speaking with any real authority on the subject, I think that I have absorbed enough information to be able to discuss the concepts herein with some semblance of competence.

In another interesting course, I was introduced to the concept of “theory of mind” in terms of literature. When I read about this concept I immediately went back and re-read my meandering mini-thesis on atheism and the mind, sure now that I had one more tool to better discuss the concept.

Let me make one thing clear: these ideas are not mine to claim ownership over. While I do pride myself on the fact that I, over the years, developed the ideas in here on my own, I am not the first person to think of them, ever. I am sure that over the years I ran into literature discussing these ideas, as well as participated in discussions that informed me. In that sense, I am sure there are numerous sources I am not crediting in this post that deserve it.

I have a Bachelor of Arts in Literature, which really gives me the credibility to do little more than muse on the subject at hand. That said, it is of intense interest to me and over the years I have done much with the subject. What you see below, again, are generally my interpretations of the information and any sourcing is the means to support the conclusion at which I have arrived.

My Goals

So, if you haven’t read my post entitled About Me: Atheism, I would suggest doing so. It will give context to my views on religion. I wrote it with the explicit purpose of it being a primer for this post. If you don’t, then don’t blame me for what happens. (Hint: total protonic reversal.)

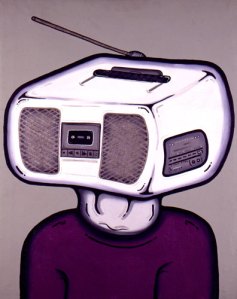

I’ll make reference to something I used in that post: the idea of God as a radio signal and us as radios (or, if you prefer something less weird, as having radios in our head). It has been my long-standing assumption that some of us—like me—just cannot receive those signals. Others—the religious among us—are receptive to these signals.

Now let me also point out here that I am not arguing, above, whether or not those signals are being sent by god or created by our own brains. I am simply going to be making arguments in support of my assumption that some of us are not equipped to hear God. The discussion of whether God is actually out there is one that I don’t care to undertake for myself. Not now at least.

A Discussion of Theory of Mind

Theory of mind is a concept to which I cannot do full justice in just a small portion of this post. Even dedicating numerous posts to it, the idea of theory of mind is still quite complex and I would probably butcher it. I’ll refer you, in that case, to the Wikipedia entry for theory of mind, which has a decent explanation and the usual links to other resources.

In short, however, theory of mind is the ability to attribute motivations to others. It is the innate social ability within (most of) us that allows us to see another person’s disparate actions and, from those actions, infer what his intentions and thoughts might be. Theory of mind is not empathy, though they are in some ways related, but rather the ability to attribute intention to another person’s behavior.

For those who find analogies helpful, here we go: consider, if you will, the physical laws that describe planetary motion. When Kepler observed the planets he observed a series of unrelated motions and actions that, at first glance, were a disordered mess. When Kepler created his three laws of planetary motion he used them to describe the behavior that the planets followed.

When Kepler wrote these laws down the planets did not suddenly start obeying them; nor were the planets, the whole time before the laws were written, following some math in their head. No, the planets were agents that followed certain patterns caused by the way our universe works. Kepler’s laws describe those motions. Planets do not have motivations, but in this analogy the laws describe the intentions of the planets. (Scientists among my readers will, hopefully, forgive me for being a bit over-simplistic with these ideas.)

So theory of mind is what allows you to see your friend, Jack, and infer from his actions that he is lonely, or hungry, or tired, or whatever it might be.

Conversely, it may help to think of those times that theory of mind fails us. Consider yourself walking down a sidewalk in a direct collision course with another person. In your mind you decide to sidestep right, figuring that this person will do the same. When you do, he sidesteps left, such that you both are still about to run into each other.

I think every one of us has probably experienced this at some point, and it is a great example of failure of theory of mind. You, in this case, tried to attribute mental states and motivations beyond your own to this person and failed.

The process by which theory of mind really explains behavior is far more complex. It, in essence, consists of us seeing action we need to describe, using our own experience with ourselves and other people, and then making inferences and applying them. The process happens in a way that we do not really realize that we’re doing it.

Finally, theory of mind has a type of filtering process built in, in that we do not apply those same things toward a tree. When you walk toward a tree you do not apply to it mental states and feelings, you know that if you don’t move it won’t. Thus, theory of mind has still worked, in this case just to tell you “that thing isn’t a person”.

Theory of mind is an innate and absolutely necessary social tool for humans. Some of us have run into someone so unpredictable that we cannot fathom what he/she is thinking or intending, and no doubt those situations were extremely frustrating. Without theory of mind we would all be unable to assume intentions, thoughts and desire even exist in someone else, much less apply these states.

Socialization is absolutely necessary for theory of mind. Just as with any other skill, practice will help you become good at it. But, beyond this, we must experience a range of emotions, thoughts, desires and pretend states to build a kind of dictionary of human behavior.

Astute readers may notice that in the above paragraph I included the phrase “pretend states” where that phrase has previously not appeared. Indeed, our ability to pretend is considered fundamentally tied to theory of mind, in that pretend is our ability to infer the mental states of others, and then act as if we were that person.

Autism

Autism prevalence (incidents per X amount of people) has increased something like 600% in the past two decades, so it is no surprise that autism is a subject of intense study. In the case of the various advancements in understanding of the human mind and the brain, it is often through the study of the atypical that we can figure out how the neurotypical (from here on out, NT) truly function.

Being that I have a degree in literature, I’m taking the time to again emphasize that I will not do full justice to autism and autism spectrum disorders (ASD). This is meant to provide the basic information necessary to comprehend the rest of the article. There is far more to autism than what I am about to describe.

Anyway, the brief description of autism is that it is a neurological disorder that causes impaired social interaction as well as impaired communication and developmental abilities. Those with autism typically have difficulty relating to others and, in fact, seem to have an underdeveloped or non-existent theory of mind.

Additionally, autism and ASD tend to manifest themselves in specific behaviors, such as resistance to change, ritualistic behavior (in this case, highly specific patterns of behavior from which the person does not wish to deviate, not ritualistic in the sense of religion) or other compulsive behavior.

Wikipedia points out that autism is “highly variable” as so no one case will be the same as the others in how it manifests, so keep in mind that not every case will have all of these behaviors. Nonetheless, the things I described above are some of the key commonalities between most cases, as well as those behaviors most relevant to the discussion at hand.

Autism and Theory of Mind

Within autism and ASD, there is a tendency to associate the social symptoms to the inability or underdeveloped ability of the autistic person to mindread (unfortunately, this term is merely the way people describe “engaging in theory of mind tasks”, and not some super cool superpower). One of the early studies in this area, Baron-Cohen et al. (1985) tested 61 children with autism, Down Syndrom and some NT children as a control.

This study used an aspect of theory of mind called false belief—the ability to understand that different people can have beliefs about the world that are different from yours—to test whether theory of mind was present in these children.

The task involved two dolls, Sally and Ann. After ensuring the children could tell the difference, the researchers took sally and had her hide a marble under one of two baskets. Sally then “left” and Ann, that devious bitch, would move the marble to the other basket. The question the researchers then asked, when Sally returned, is where Sally would look for her marble. The correct answer, my friends, is under the first basket. The answer coming from the children with autism? The second basket.

For those not sure how this proves anything, it is a very watered-down test of mindreading and false belief. Assuming you, the reader, are an NT individual, you would know that Sally wasn’t aware Ann moved the marble, and thus when looking for it would look where she left it.

The failure for the autistic children to understand this was some of the earliest support that their theory of mind was not working in the same way as ours—if at all. They cannot attribute to Sally the idea that she thinks and sees things different from themselves, and thus believe Sally would have looked where the marble was. These deficits in theory of mind occur early on in life, usually from about the first year and beyond.

The social difficulties of the person with autism stem from a lack of or underdeveloped theory of mind. As I described before, the theory of mind within us allows us to understand that the tree we see does not have intentions.

Imagine, however, that you were to lack theory of mind. Not only would you not be able to attribute intentions to the tree (rightly), but you would not be able to do so to your family. Because the person with autism cannot mindread the people around him, he instead sees them in the same way we would see another inanimate object, as lacking any emotional states.

You can imagine, then, how unnerving it would be if the tree I have used for examples were to, suddenly, stand up and begin to walk around, talk, and act upon you. In the same way that we would be terrified or confused by this, the person with autism sees the social behaviors of those around him as other objects acting in unpredictable ways.

So to recap: autism and ASD affect the theory of mind starting at early ages—as early as one—and continue to cause deficits in the applications of mindreading within autistic children. As such, they are not able to attribute states to other people, objects, etc. That last line is quite important. Maybe I should have bolded it.

Theory of Mind and Religion

In the ever-continuing quest for explanations, science has begun to notice that there are a few interesting things about theory of mind in relation to religion. While there are many attempts to “explain” religion, keep in mind that there is still that fundamental aspect of faith that will never go away. Nonetheless, one of the ways that science is applying theory of mind is to help explain religion.

In the same way that we ascribe behaviors and desires to other people, theory of mind does allow us to attribute these causes elsewhere. I talked about how we do not assume a tree has a desire, and so we don’t need to apply theory of mind there.

But humans are, if nothing else, creatures that like to know why things happen. More than that, they notice patterns in behavior where there isn’t necessarily anything to which to attribute cause. Think, if you would, about sitting on the grass and staring at the clouds. We look at those and see shapes in them. Similarly, people have seen and attributed shapes to stars. People see a man in the moon. (In a pretty interesting story, people used to talk about the man in the moon, but it wasn’t until I saw a diagram of what you’re supposed to see—at the age of 21—that I was finally able to see him.)

Is that cloud actually shaped like a car or is there actually a face on the moon? Not really. That cloud may bear similarities to a car, but it is, in fact, your mind applying order to the unordered. It is a human tendency, and it is, I would argue, strongly related to theory of mind.

While we know that there are no intentions behind that cloud, that it cannot wish to be shaped as a car, we can use theory of mind to apply pretend states to it. In the same way, we often look at disparate events happening within a certain timeframe as evidence of bad or good luck. Does luck actually exist? Probably not. It just so happens that your mind is really good at ordering the disordered.

Is this an extension of theory of mind? Probably to some extent. In the same way that we look at a person’s disparate actions and attribute emotion or cause to it, we too look at those “unlucky” events and assume some force was responsible for it: thus, we create luck.

So how does this tie into religion? Consider early man in a pre-literate but still verbal society. In order for societies to exist, there had to be some form of theory of mind or people could not cooperate (if you can’t tell what someone is going to do, or attribute mental states to a person, you’re not going to be useful in helping him—if you even want to).

Now think back to things like, say, thunder or lightning. Or, perhaps, the weather as a whole. While we know now that the weather isn’t affected by our personal actions, this early society would have no way to know that. Indeed, in the same way that we think of luck, these people could easily have seen a pattern in the weather and attributed it to something they did. Thus, they began ritual behavior to appease the unknown force that they had pleased or angered.

If this sounds like a very simple religion, that’s because it is. In essence, these early people would have recognized patterns and attributed to some unseen entity mental states akin to their own.

Please note: I am not saying this is at all how religion formed, but giving you an example of how theory of mind could, in this hypothetical society, lead to the creation of an ersatz religion.

I’m also describing in this situation the reverse order by which religion tends to happen today. In the New Scientist article I linked above, there is indication that theory of mind is used to interpret a god’s intentions and feelings in terms that we can understand. Because we hope to figure the intentions of others, it is only natural that we then apply this to our deities, as well.

Emerging neuroscience is beginning to show this link, as well. In a study of religious individuals using an fMRI and a series of religious factors the study found that “God’s perceived involvement appeared to activate brain circuits very similar to those activated in Theory of Mind tasks.” God’s perceived emotion, one of the areas tested, activated areas of the brain “known to be activated when processing emotional Theory of Mind” information.

Using Christianity as an example—because it is well known and probably the religion of many of my readers—it is easy to see why theory of mind would work with God. The Old Testament God was one described in terms of human emotions—he was angry, wanted retribution, pleased, etc.

Indeed, when thinking of God we do so in human terms. Part of this, one could argue, is because He is so far outside of our understanding that we need a framework of humanity to understand him. This may well be, but it could also be that God was born from the attempts to explain events in the world using theory of mind.

Whatever the cause is, whether religion is real or not, we do perceive of God in human terms. In order to do so, one needs a functioning theory of mind, otherwise God would likely disappear, and instead one would see a series of unrelated, random events.

Does that sound a little like the way some people view the world? Interesting.

Keep tuned in, readers, for the continuation of this in tomorrow’s update, in which I will link all of this together with atheism.